A Transitional Flag

The following was my entry to the An Tir 2025 Kingdom Arts and Sciences Championship. It was a single entry, so I was not eligible to become champion. However, I earned the rank of Scholar of An Tir.

Introduction

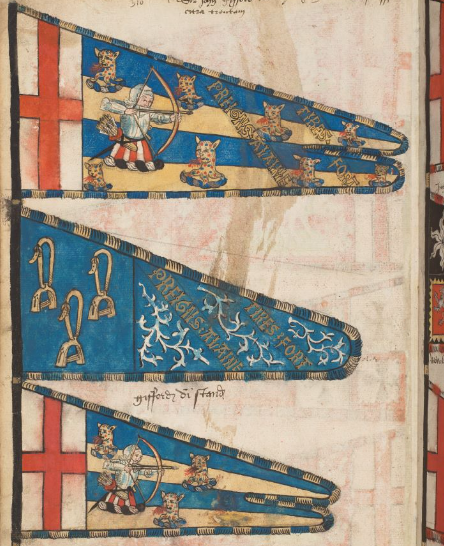

In June 2021, I reviewed a manuscript from the early 1530s by Sir Thomas Wriothesley, Garter King of Arms1, as research on categories of pre-17th century flags. The manuscript included several pages of Tudor flags, including banners, standards, and guidons, which were useful to illustrate my articles. They also included a dozen flags in a style I had not previously come across.

Similar in shape to a guidon but bearing none of its identifying features, this mysterious flag defied categorization. As it was beyond the scope of my project, I took screenshots of some examples of the flag and set them aside for further research.

When I returned to it later that year, I found that none of my available resources had anything to say on the matter. Unfortunately, like most details of medieval vexillology, there is almost no scholarly work about this flag form. Beyond its appearance in a few contemporary records, there is no record of its actual use and intent. Indeed, there is not even a clear name for this type of flag! However, in exploring its place within the greater family of late Tudor and early Stuart flags, one may gain a better understanding of both flag design and late-period English pageantry.

Basics of Flags

For this discussion, it is important to cover some common terms, and the identifying features of known flag categories.

A Brief Taxonomy of Flags

- Banner – A banner is a square or tall rectangular flag that exclusively displays the arms of the owner.

- Pennon – In the Middle Ages, a pennon was a long, tapering flag, usually triangular or swallow-tailed. Like banners, they displayed the arms of the owner throughout the flag. With the popularity of badges in the 15th century, examples of pennons displaying badges of royal houses began to appear.

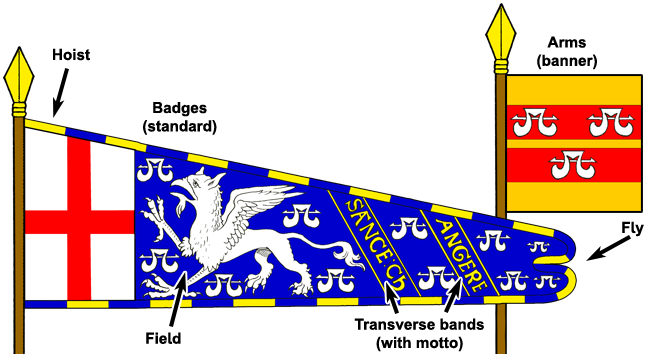

- Standard – A standard was originally a larger form of pennon, displaying the arms of the owner. However, with the rise in popularity of heraldic badges, the late medieval and early Tudor version of the standard featured a badge of allegiance in the hoist (the red cross of St. George on a white field for those loyal to England), a field in the color(s) of the owner’s livery, one or more badges repeated across the field, and either transverse bands, mottoes, or both.

- Guidon – A simplified version of the standard, a Tudor guidon had the badge of allegiance at the hoist, a field of livery, and fewer badges repeated across the field. Transverse bands or mottoes are vanishingly rare.

- Gonfalon – An adaptation of the ancient Roman vexilla, a gonfalon is a processional flag, decorated only on one side, and hung from a horizontal bar, which in turn is held up by a vertical pole. While sometimes used to display primarily armory, this type of flag is more often decorated with ecclesiastical imagery2.

Flag Glossary

- Arms are a design particular to the owner, and used for personal identification. Often arms are inherited, and an individual may display multiple arms to which they are entitled, using a process called quartering.

- A badge is an insignia used to mark an individual’s servants and retainers.

- The field is the background of the flag.

- The fly is the part of the flag furthest away from the pole.

- The hoist is the part of the flag closest to the pole.

- A transverse band is a diagonal stripe that appears on some flags. They sometimes appear plain, but just as often carry the owner’s motto.

Wriothesley’s Mysterious Flag

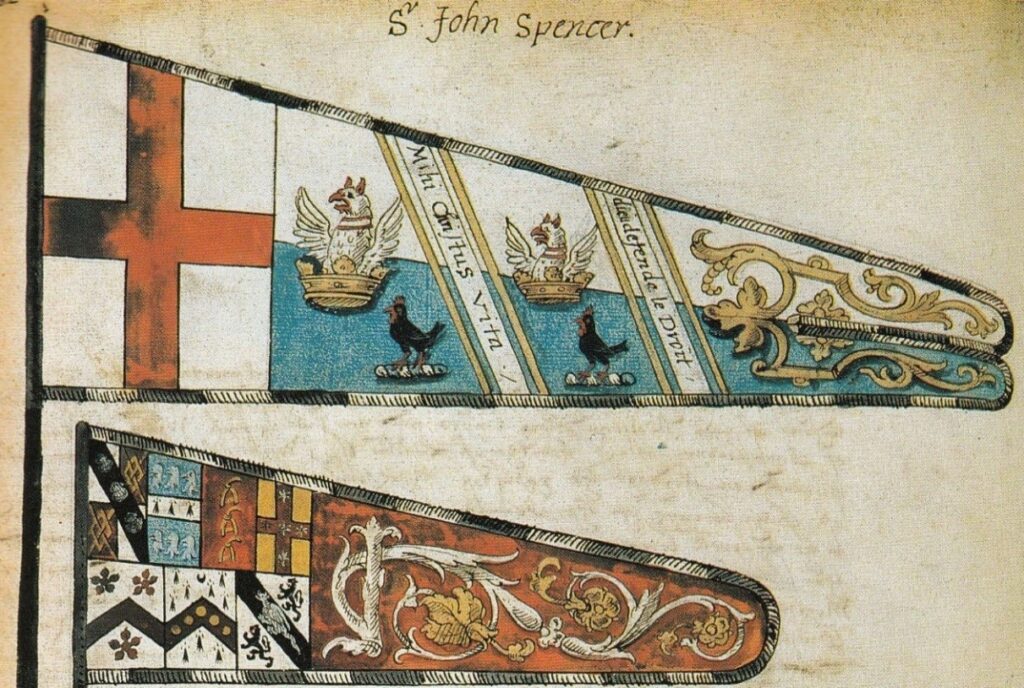

In Wriothesley’s manuscript, we see examples of banners, standards, and guidons, as well as the flag type that is the focus of this paper.

Identifying features of this mystery flag include:

- Long tapering design

- Arms in the hoist

- Blank, uncharged field, often decorated with floral diapering

- Transverse bands with mottoes

Fitting the Elements into the Taxonomy

In comparing the defining features of this flag to that of the established model, we find that the design is not conclusively one thing or another. The flag is in the shape of a guidon, but has transverse bands and mottoes like a standard. It displays the arms of the owner like a banner or pennon, but most of the flag’s design is taken up by a blank field.

Absent a clear fit into one model or another, we may deduce what kind of flag this is by process of elimination. Banners in this manuscript are always square, so the tapered flag is clearly not a banner. Instances of this flag always appear in the manuscript alongside at least a standard, and usually a guidon as well, so it is neither of those. Having eliminated the other options, we may deduce that this flag is, in fact, a pennon.

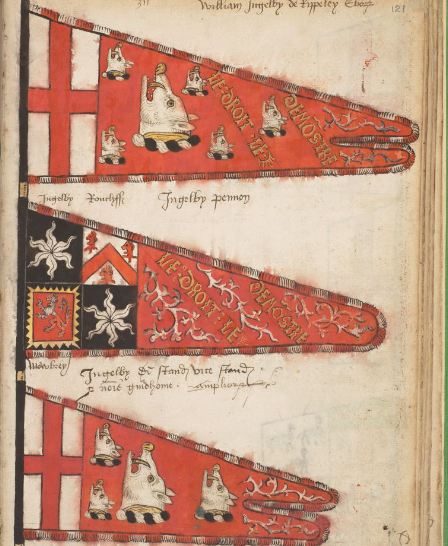

This assumption is validated by a note above one of the instances, the flags of Ingelby, in Wriothesley’s own hand.

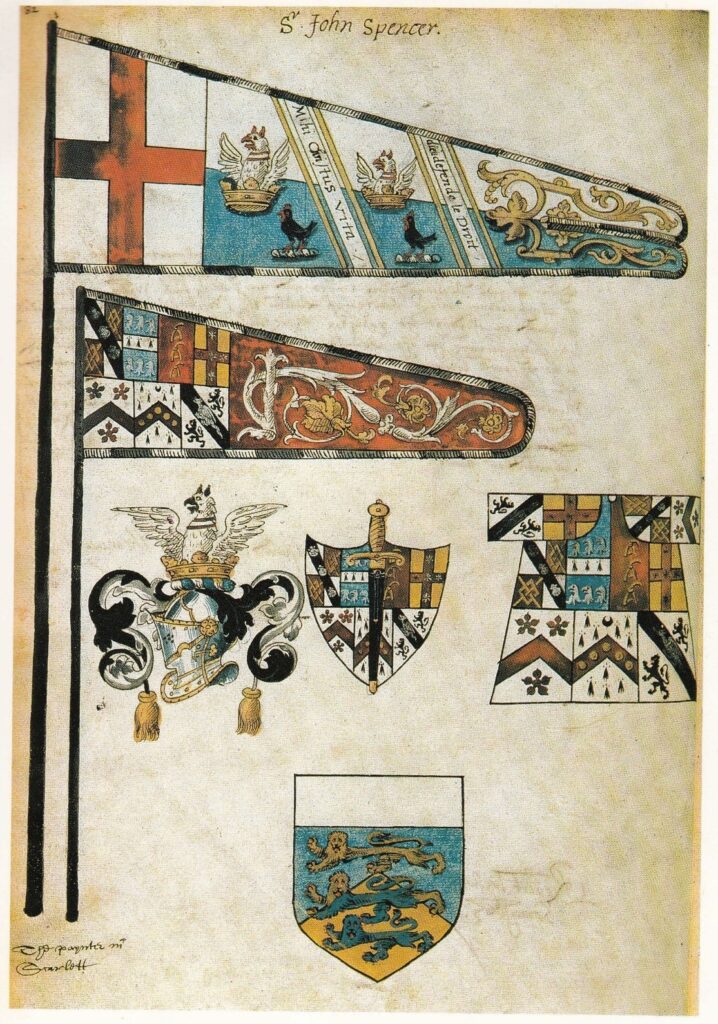

The only contradictory label that I was able to find for this flag type, and indeed the only mention of the flag that I was able to find in any standard resource, is long post-period. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry has a plate (see Appendix B) reproducing artwork from 1600 with a modified version of the mystery flag, this time with no transverse bands and a distinctive acanthus vinework issuing from a single branch at the hoist (see figure 7). The authors label it “Funeral certificate of Sir John Spencer of Althorp, Northamptonshire, Kt., d. 9 Jan 1599/1600, showing a standard, guidon, helm, mantling and crest, shield, and tabard, painted by Richard Scarlett (d. 1607) (Coll. Arms, I 16, p.82).” However, they provide no source for this term, nor any discussion on the nature of the flag within the book. The only labels on the plate itself are “Sr. John Spencer,” and the artist’s credit.

I posit that Woodcock and Robinson chose this label based on the shape of the flag and an understanding of modern flag forms (which will be discussed more thoroughly in the next section), and not a reflection of research into Renaissance-era flags. Based on the label provided by Wriothesley, for the rest of this essay I will refer to this peculiar flag form as a “Tudor pennon.”

Form Follows Function: The Knight Banneret Ceremony

Having positively identified this flag as a pennon, we may address the differences between the earlier form and the Tudor model. Most notably, the Tudor pennon distinguishes itself from the medieval form in that the field is divided between the arms in the hoist and the decorative fly, which carries no armorial content. What might have prompted this design change?

Since at least the 14th century, English knighthood has distinguished between two ranks; the lower status of bas chevalier, or bachelor knight, and the higher status of knight banneret. A key mark of the latter rank, as indicated by the name, is that while bachelor knights are allowed to fly a pennon, knights banneret are entitled to fly a banner.

In Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, he describes the ceremony of making a knight banneret:

Sir John Chandos advanced in front of the battalions with his [pennon] uncased in his hand. He presented it to [Edward the Black Prince], saying: “My lord, here is my [pennon]: I present it to you, that I may display it in whatever manner shall be most agreeable to you; for, thanks to God, I have now sufficient lands to enable me so to do, and maintain the rank which it ought to hold.” The prince, [King Peter of Castile] being present, took the [pennon] in his hands, which was blazoned with a sharp stake gules on a field argent: after having cut off the tail to make it square, he displayed it, and, returning it to him by the handle, said: “Sir John, I return you your banner. God give you strength and honour to preserve it.”3

John Guillim’s A Display of Heraldrie, in his description of knights banneret, affirms not only that the rank was in place through the Tudor period, but also that removing the end of the pennon was an integral part of the ceremony.

The King (or his General, which is very rare) at the head of his Army (drawn up. into Battalia after a Victory) under the Royal Standard diſplayed , attended with all the Field Officers and Nobles af the Court, receives the Knight led between two renowned Knights or valiant Men at Arms, having his Pennon or Guydon of Arms in his Hand; and before them the Heralds, who proclaim his valiant Atchievements, for which he deferves to be made a Knight Banneret , and to diſplay his Banner inthe Field ; then the King (or General) ſays unto him, Advances toy Banneret, and caufeth the point of his Pennon to be rent of; and the new Knight having the Trumpets before him founding, the Nobles and Officers accompanying him, is remitted to his Tent, where they are nobly entertained.4

For pennons of the 14th century, this ceremony presented an interesting design challenge. Pennons were typically triangular, with the arms displayed all the way through the design. Cutting off the tail would remove a portion of the arms themselves, and cutting it to a relative square would remove so much of the arms as to render it unrecognizable. Pennons were also frequently displayed “at charge,” or oriented so that they appear accurately when the spear or lance is horizontal. This is different from banners, which are always designed to display with the pole upright.

These changes all indicate that the early 16th century version of the pennon was designed, if not specifically to be used for the creation of a knight banneret, then at least with an awareness of the particulars of that ceremony.

Irish Funerary Records and the Evolution of Flag Forms

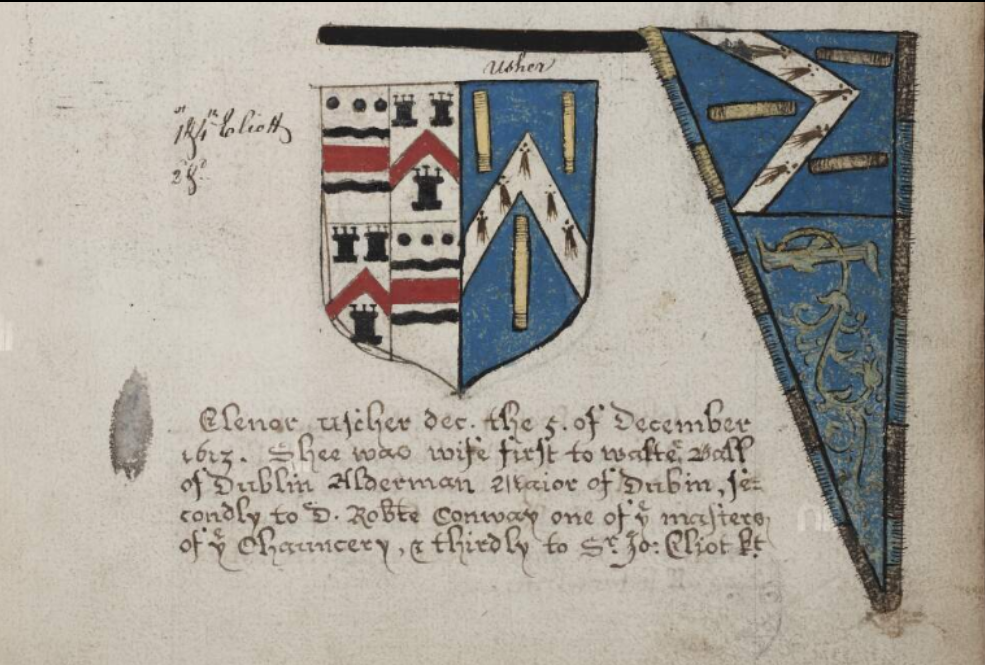

In trying to determine whether Wriothesley was documenting an existing practice or instead proposing a new form of pennon, I discovered evidence of period usage in late 16th and early 17th century Irish funerary records, which depicted every form of armorial display at the funeral service. Ireland was a vassal state of England at the time, having been conquered by the Tudors over the course of the 16th century, and their nobility was either of English stock or heavily influenced by English forms of armorial display5.

In the records, we see standards, guidons, and banners in forms unchanged from 1530. We also see tapered flags with arms in the hoist and distinctive floral diapering in the fly, using the same acanthus vine and upright branch seen in the funerary pennon of John Spencer from 1599 mentioned in the previous section. A catalog of these examples may be found in Appendix C. These designs are most assuredly iterations of the Tudor pennon. Notably for this manuscript, the majority of Tudor pennons have floral diapering but no transverse bands, similar to Spencer’s design.

More interestingly, we see other pennon-shaped flags with arms in the hoist, but with more characteristics of Tudor standards and guidons in the fly, especially in the inclusion of both transverse bands and badges.

This further modified form of the pennon is notable because it is more or less identical to the modern form of a standard: arms in the hoist, badges, transverse bands and mottos in the fly, with a rounded, guidon-like tail. Compare this design with the standard of Brian Arundel, issued in 2002 by the College of Arms:

Conclusion

In this exploration of Wriothesley et al, I discovered a form of flag that has little to no existing academic literature, classified it, discovered its probable causes for evolution, marked its likely use in knight banneret ceremonies, and used it to link medieval and modern flag practices. While my research on Tudor pennons is far from over, I am excited to share my preliminary findings with the Known World.

This research into Wriothesley’s peculiar flag took several turns I did not expect. As with all research into pre-modern vexillology, the lack of reliable resources on flag design and the dearth of interest in the topic by modern scholars will continue to hinder further exploration. However, I hope that my own small efforts in this field, both in research and publication, will see a renewal of enthusiasm into the subject of period flag design. And as more period manuscripts and extant flags are discovered, I hope to continue to revisit my hypotheses and test them against new knowledge.

Appendices

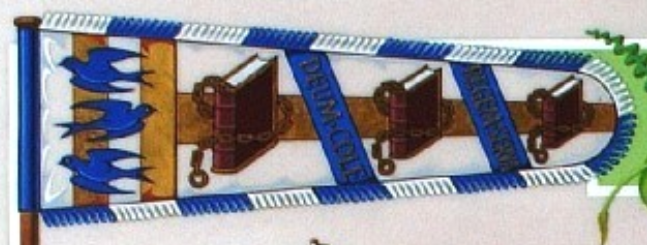

Appendix A: Examples from Wriothesley Heraldic Collections, Volume II, Add MS 45132.

Appendix B: Plate from the Oxford Guide to Heraldry

The image below is from the Oxford Guide to Heraldry (2001) by Thomas Woodcock and John Martin Robinson. It is captioned:

“Funeral certificate of Sir John Spencer of Althorp, Northamptonshire, Kt., d. 9 Jan 1599/1600, showing a standard, guidon, helm, mantling and crest, shield, and tabard, painted by Richard Scarlett (d. 1607) (Coll. Arms, I 16, p.82).”

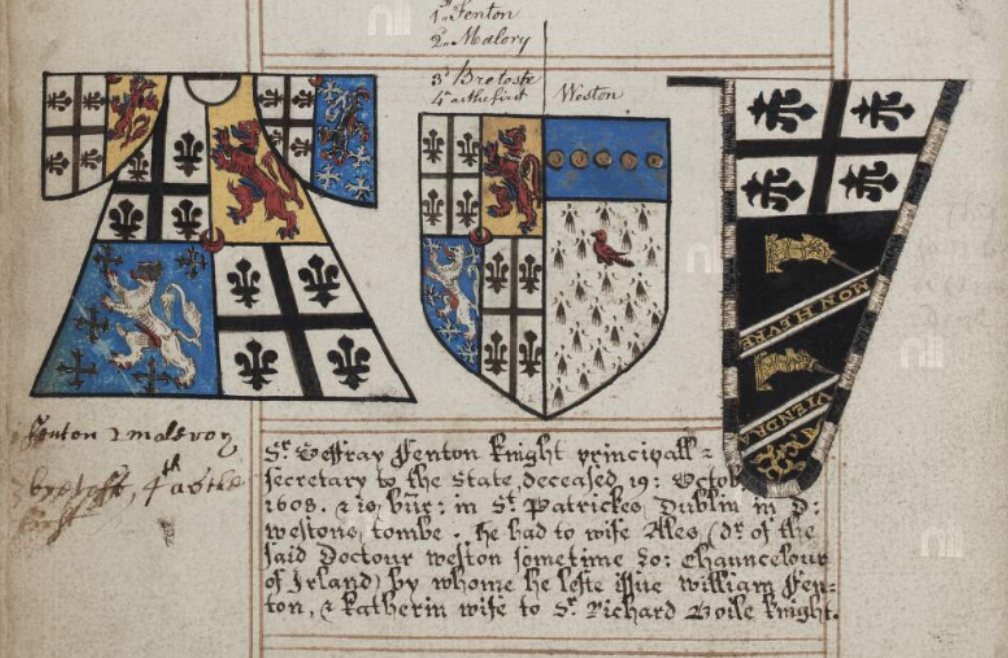

Appendix C: Examples from Funeral Entries Vol. 3

This record of funeral entries, dated between 1607 and 1620, features drawings of armorial display that appeared at the funeral.

23 funerals feature the most common set, displaying a tabard, escutcheon, and pennon:

9 examples feature just a pennon and escutcheon.

4 examples feature variant pennons with badges and transverse bands.

14 examples feature more complex displays, adding multiple escutcheons, standards, guidons, banners, helms, and crests.

Locations of cited examples with the date of the funerals:

Tabard, Escutcheon, Pennon

Fol. 6r – 1607

Fol. 7v – 9/1607

Fol. 32r – 1/1611

Fol. 34v – 1612

Fol. 35r – 8/1612

Fol. 36v – 10/1612

Fol. 39v – Unknown

Fol. 40v – 8/1613

Fol. 42v – 3/1614

Fol. 50v – 4/1615

Fol. 57r – 7/1616

Fol. 58r – 8/1616

Fol. 58v – 9/1616

Fol. 59r – 11/1616

Fol. 61v – 2/1616

Fol. 66v – 7/1617

Fol. 86r – 12/1619

Fol. 88r – 1/1618

Fol. 89v – 3/1619

Fol. 114r – 3/1622

Escutcheon, Pennon

Fol. 41r – 12/1613

Fol. 41r – 9/1613

Fol. 64v – 6/1617

Fol. 72v – 3/1617

Fol. 76r – 12/1618

Fol. 76v – 12/1618

Fol. 83v – 9/1619

Fol. 97r – 6/1620

Fol. 99v – 11/1620

Tabard, Escutcheon, Pennon with bands and badges

Fol. 14v – 10/1608

Fol. 19r – 1/1609

Fol. 23r – 4/1610

Fol. 32r – 8/1611

More Complex Displays

Fol. 26r Unknown

Fol. 33r 2/1614

Fol. 69r 8/1617

Fol. 41v 11/1613

Fol. 46v 11/1614

Fol. 48v 4/1615

Fol. 54r 4/1616

Fol. 61r 1/1616

Fol. 42r 1/1613

Fol. 46r 11/1614

Fol. 60r 12/1616

Fol. 85v 10/1619

Fol. 94r 6/1620

Fol. 98v 11/1620

Appendix D: Grant of Arms for Brian Arundel, issued 2002

Works Cited:

Primary Sources:

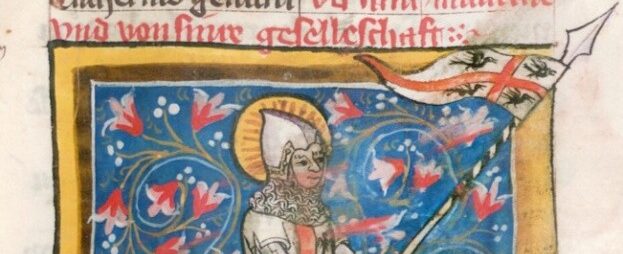

De Voragine, Jacobus. Legenda sanctorum aurea, verdeutscht in elsässischer Mundart [u.a.] – BSB Cgm 6, [S.l.], 1362 [BSB-Hss Cgm 6], p. 162. https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0004/bsb00043859/images/index.html?id=00043859&nativeno=162

Froissart, Jean. Chronicles of England, France, Spain, and the Adjoining Countries: From the Later Part of the Reign of Edward II to the Coronation of Henry IV, translated by Thomas Johnes. London: H.G. Bohn, 1857. P.370

Ireland. Genealogical Office. Funeral Entries, Vol. 3, Containing Armorial and Genealogical Notes Made By Officers of Arms Concerning Deceased Persons, With, in Some Cases, Illustrations of Their Arms and Funeral Processions. 1604-1622. https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000529284, Fol. 6r-114r

Wriothesley, Thomas. Wriothesley heraldic collections, volume II (Add MS 45132), c. 1530, from the British Library digitized manuscripts, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_45132, fols. 29v.-122v

Secondary/Post-Period Sources:

Guillim, John. “Of Knights Bannerets.” A display of heraldrie: London, 1611. Norwood, N.J, Amsterdam: W.J. Johnson ; Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1979.

Moody, T. W., F. X. Martin, and F. J. Byrne. A New History of Ireland: Early Modern Ireland 1534-1691. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Inc, 1991.

Rhodes, Kevin. “Heraldic Flags.” Heraldry at Poore House, May 22, 2022. https://herald.poore-house.com/display/heraldic-flags/.

“The Arms and Crest of Brian Arundel, 2002.” College of Arms, April 5, 2013. https://www.college-of-arms.gov.uk/news-grants/grants/item/69-arms-granted-to-brian-arundel.

Wagner, Anthony. Heralds of England: A History of the Office and College of Arms. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1967, p. 40.

Woodcock, Thomas, and John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2001. Plate 27

Additional Bibliography:

Gayre of Gayre and Nigg, Robert. Heraldic Standards and Other Ensigns: Their Development and History. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1959.

Smith, Whitney, et al. Flags Through the Ages and Across the World. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

- The senior of the three English Kings of Arms. Anthony Wagner, Heralds of England: A History of the Office and College of Arms. Cambridge University Press, 1967. p.40.

- I include gonfalons in the taxonomy for completeness; this flag style does not appear in any of the primary resources used by this essay

- Jean Froissart, Chronicles of England, France, Spain, and the Adjoining Countries: From the Later Part of the Reign of Edward II to the Coronation of Henry IV trans. Thomas Johnes (London: H.G. Bohn, 1857), p.370.

- John Guillim, “Of Knights Bannerets.” A display of heraldrie: London, 1611. Norwood, N.J, Amsterdam: W.J. Johnson ; Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1979.

- T. W. Moody, F. X. Martin, and F. J. Byrne. A New History of Ireland: Early Modern Ireland 1534-1691. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Inc, 1991.