This article marks the start of a series of articles covering the various types of heraldic flags found in the Middle Ages, providing enough of an overview to their use to inspire the reader to design and paint their own. Each article will describe the distinguishing features of the flag type, including their typical use in period, using examples from period art where available. At the end of the article, I will guide the reader through the process of designing a new flag using armory appropriate both to the SCA and history. We start this series with the largest of the heraldic flags: The standard.

Standards and guidons are long, tapering flags that frequently end in a rounded, split fly. The flags feature the livery colors, badges, and motto of said flag’s owner. The two flags are very similar, with the main difference being the rank of the bearer (the standard being limited to certain ranks in period) and the size of the flag (the guidon generally being smaller and almost never featuring a motto).

Standards were found in various permutations throughout Western Europe and beyond in late period. This article largely uses Tudor standards as examples but seeks to make accurate statements about standards generally.

Standards were massive flags that served as rallying points for armies and retainers. According to Tudor sumptuary law, standards were up to four yards in length for a bachelor knight, increasing by rank up to a full twelve yards long for the king.

What goes on a standard?

Standards, particularly English standards of the the 14th-16th centuries, had seven parts:

- The hoist of allegiance

- The livery field

- The fringe

- The primary badge

- The secondary badges

- The transverse bands

- The motto

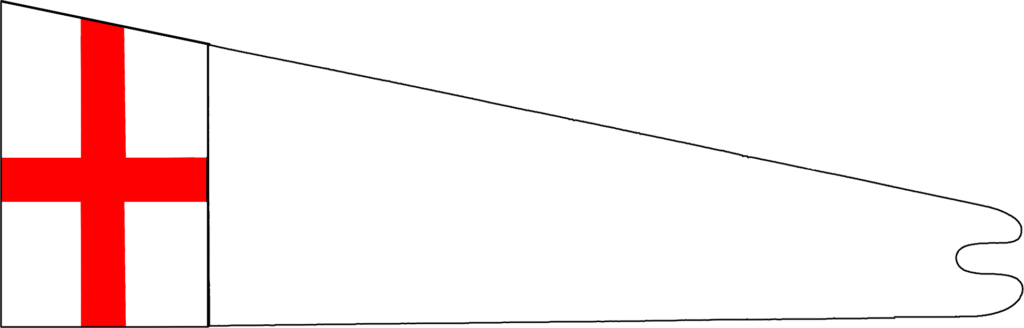

Hoist of Allegiance

The hoist of allegiance is a display of the kingdom’s populace badge in the hoist, or part of the standard closest to the flagpole. Hoists of allegiance were used to indicate the owner’s primary loyalty, and was a unifying symbol in times of war to show whose side of the conflict the bearer was on. In the perennial wars between England and France, for example, a red cross on a white field indicated allegiance to the English throne, while a white cross on a blue field demonstrated allegiance to the French Crown.

Not all standards utilized the hoist of allegiance, and not all kingdoms or sides of major wars had a unifying symbol that could be employed as one, but they appear to be near-universal in English examples.

Livery Field and Fringe

The livery field displays of the owner’s livery, or the colors they use to outfit his servants. The field is most commonly solid, but is sometimes divided into two, three, or four parts by horizontal lines of division.

While usually plain, we do have some examples of complex lines of division, such as the wavy bars of Edward Guilford, below.

Livery was usually limited to one or two colors, usually but not always mirrored by the fringe around the edge of the flag. Livery was usually constrained to heraldic tinctures. However, in “Banners, standards, and badges, from a Tudor manuscript in the College of Arms,” we have a few examples of murrey (maroon), tawny/tenne (orange), and russet (brown) livery fields, as well as one labeled “sky blue,” a color usually blazoned in heraldic tracts as bleu-celeste. One page of the manuscript features the standard and guidons of the Earl of Northumberland whose livery is russet, yellow, and tawny. Below, the standard of Sir Griffithe Ap S. Res fitz Uryan features a field parted murrey and blue. The standard of Gregory Care features a field barry of four tawny and yellow.

Primary Badges

Like livery, badges are symbols that the standard’s owner uses to label his servants and supporters. The standards of the Lancastrian kings, for example, feature a red rose, while the Yorkist kings usually displayed a white rose en soleil. Supporters of the York and Lancaster lines wore these badges during the Wars of the Roses. For examples of each, see the standards of Henry V and Edward IV, below.

There is usually a large primary badge near the hoist and smaller secondary badges strewn across the rest of the field. The larger badge is sometimes a supporter from his achievement placed in a statant or passant posture. Below, another standard of Edward IV features the white lion of March that he used as a supporter.

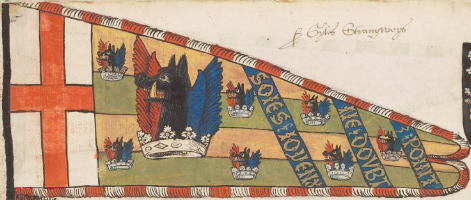

The primary badge can also be the owner’s crest. Below, the standard of Master Giles Strangways features his winged boar’s head crest.

The layout of badges on standards and guidons follows a few different patterns. Most commonly for guidons, the flag might have only one instance of the primary badge near the hoist with no other badges, as in another standard of Henry V.

However, the most common layout for badges on standards has a primary badge and secondary badges strewn throughout the field.

Secondary Badges

Sometimes the secondary badges are a repetition of the primary badge, as in the standard of Edward Chamberlayn which features a nag’s head.

Sometimes the secondary badge is different from the primary badge. Below, the standard of Lisle, the primary badge is the stag within a wreath, and the secondary badges are lilies.

In very rare cases in the Tudor period, standards bore multiple secondary badges in addition to the primary badge, but each secondary badge was repeated multiple times along the length of the field, and they were all badges that the owner of the used to mark their retainers. In the example below, there are two secondary charges, a red cross crosslet and a pair of red wings entwined by a blue knot.

Transverse Bands and Mottoes

Diagonal stripes called transverse bands frequently overlay the field of a standard, and are often inscribed with mottoes. The bands might be a plain stripe, a stripe outlined with a thick edge, or two thin stripes on either side of the motto text directly on the field (basically a voided band design). Generally, transverse bands on standards from the British Isles run from the viewer’s top left to bottom right (bendwise) as with the standard of Sir John Arundel below, while Continental transverse bands tend to run from the viewer’s top right to bottom left (bendwise sinister).

While the transverse bands usually feature a motto, they sometimes appear in manuscripts as blank, as with the standard of Sir Thomas Cornwall.

Mottoes usually appear in the vernacular language of the nobility; in England, most mottoes on early standards are French, while later standards feature English mottoes. They usually appear diagonally, either on the transverse bands mentioned above, or directly on the field.

Sometimes, the motto appears horizontally on the field, as with the standard of John Raynesforth.

Standards will sometimes omit the motto, leaving the bands plain, or omit the motto and bands entirely, as with the standard of Sir Robert Morton.

Guidons

Guidons are similar in shape to standards, but were shorter. This was due to their use; while a standard was used as a relatively stationary flag, the guidon was a a more mobile flag to be used on the field. Guidons were also simplified versions of standards that usually only had one badge and entirely omitted the motto and transverse bands. Lastly, guidons usually had a solid, rounded tail rather than the typical split tail of the standard.

As standards were limited only to higher ranks, a gentle raising an army might be entitled to a guidon but not a standard.

Below are five examples of some standards previously seen in this article, along with guidons that appeared below them in the same manuscript.

How do I design my own standard?

There is a tradition of SCA standard layouts which I describe in detail in another article. However, if you want to follow a more medieval pattern, let’s take a look at the parts of the standard:

Hoist of allegiance: Where does your primary loyalty lie? On what side of a war are you? The hoist of allegiance is likely going to be your kingdom’s populace badge, although using the period equivalent is a great way to represent your persona story.

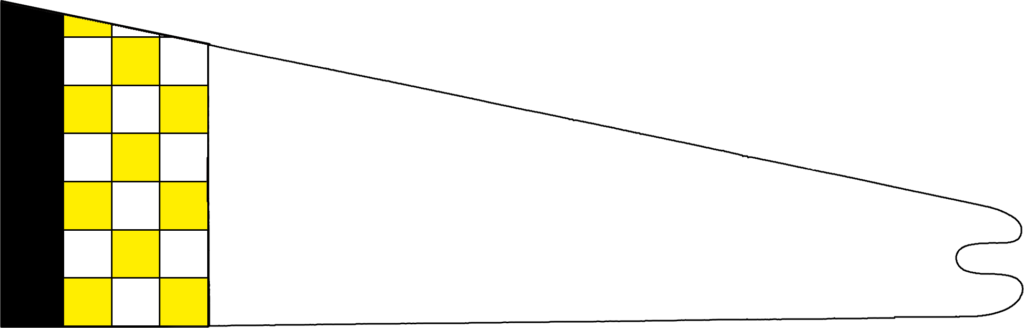

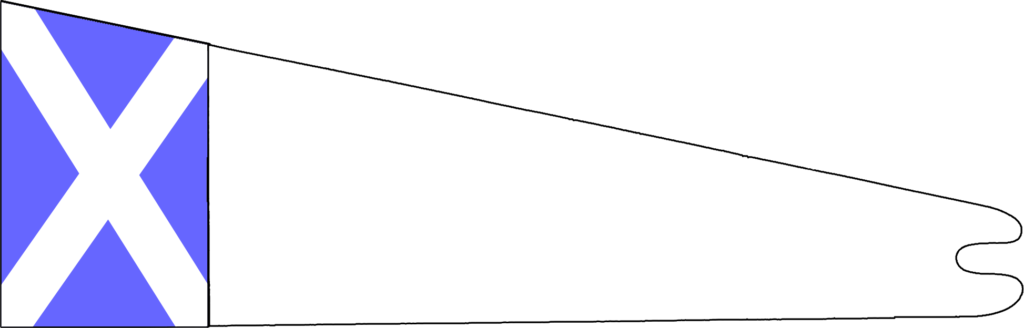

In the examples below, I’m using the ensign of An Tir (Checky Or and argent, a tierce sable) for my whimsical example, and the cross of St. Andrew (Azure, a saltire argent) for my persona-appropriate design.

Livery field and fringe: What are your favorite colors? Does your household have colors that appeal to you? If you had servants, what colors would you want them to wear? If you have one favorite color, use that as your livery field. For two favorite colors, split the field horizontally into two, three, or four parts. For three or four favorite colors, use two for the field and the rest for the fringe. You can also use the fringe to echo the hoist of allegiance or the colors of your arms.

In the examples below, I’ve chosen a solid crimson field (my favorite color) for the former, and goldenrod and white (my household colors) for the latter. I’ve also added gold and white fringe to both flags as a further nod to my household livery.

Badges: Do you have a registered badge? Do you consistently use a crest or supporter in your achievement? These would be perfect to use on your standard. Generally it’s best to use a maximum of two badge designs. If one is a supporter or full animal, place a large iteration of it near the hoist. Place multiple copies of either the large badge, or a different badge you also own/use, throughout the remainder of the flag. You may be tempted to use the transverse bands (mentioned below) as boundaries to separate different badges. Remember that the reason for the repetition is to ensure that the badges can be seen from every direction.

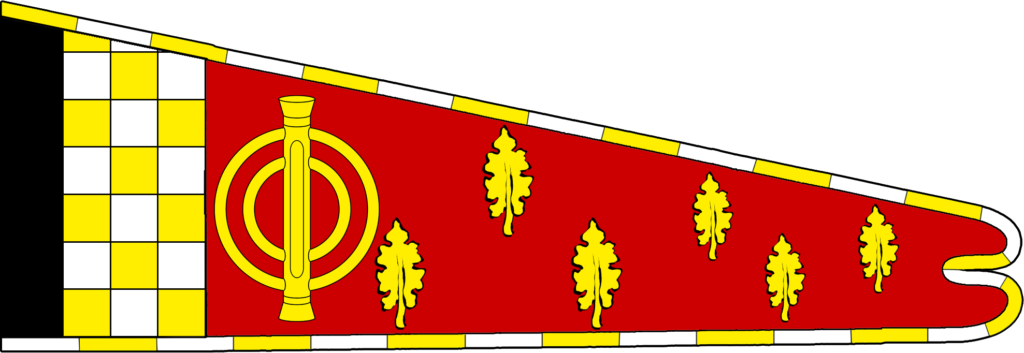

In the examples below, I chose my punner as the main badge and oak leaf for the repeated badge on the first design, while the second features my supporter (a brown bear) and crest (a brown bear’s head issuant from a baronial coronet) for the large and small badges, respectively.

Transverse bands and motto: Do you have a motto, war cry, or pithy catch phrase? Do you like to hide jokes behind the veil of a language other than the common vernacular? These are perfect for inclusion on a standard! Mottos usually appeared on transverse bands, but sometimes appeared directly on the field. Figure out what you want to say, how many bands you’ll need to spell it all out, and place the bands accordingly. Words can and do break across lines, so feel free to do so on your own standard.

In the examples below, I opted to use the British bendwise transverse bands. For the first design, I chose the Latin motto “Candor et Civilitas” (honesty and courtesy) in red letters on solid gold transverse bands. In the second design, I used voided band style in black with a French motto (appropriate for a Scots persona), “Parle Fort et Vrai” (speak loud and true).

What other kinds of heraldic flags are there?

For more information about heraldic flags, please see the options below:

Banner – A square or tall rectangular flag, used to display arms

Pennon – A smaller flag used to display arms or single badges, great for battlefield identification

Gonfalon – A processional flag hung from a horizontal pole, can display arms, full achievement with awards, artistic motifs unrelated to heraldry

Notes:

Scanned illustrations from Wriothesley Heraldic Collections, Volume II, Add MS 45132.