Recently, the SCA College of Arms developed a proposed name, badge, and item of regalia for the newly approved peerage order for ranged martial pursuits, and presented it to the Society for feedback. This rare occurrence of the heralds considering a new peerage order has only happened twice before in the history of the SCA (with the Order of the Pelican and the Order of Defense, respectively), as the other orders were created prior to the founding of the College of Arms. And this is the first time the College has been given the responsibility of designing and vetting the name, badge, and regalia, as the Orders of Defense and the Pelican had already had their names and insignia determined by the Board prior to consulting with Laurel Sovereign of Arms.

I’ve written previously about the name of the Order, Esperance 1, and how it fits within the greater scheme of Peerage Order Names. This article, however, will focus on the process of choosing a badge for a Peerage Order, and what requirements it must fulfill in order to be approved by the College of Arms.

Key Terms and Concepts

So, to begin, let’s review a few things about SCA badges.

Badge: A badge is a visual symbol used to represent ownership or affiliation. A peerage order’s badge is a sign that the person wearing it is a member of that order, just as a kingdom populace badge marks the wearer as a proud subject of that realm. Badges are usually two-dimensional, displayed upon a surface (e.g. painted, embroidered, stamped, tooled, etched, or engraved). Like arms, a specific badge is identified by the individual thing or things (heralds call these “charges“) it depicts and the arrangement that they’re in, as well as the colors (heralds call these “tinctures“) of the charges and their backgrounds (heralds call this the “field“).

As an example, the populace badge for the Kingdom of the West is “Or, a demi-sun vert,” or in plain English, the upper half of a green sun on a yellow field. If the charge isn’t a half-sun, or isn’t green, or if the background isn’t yellow, then it’s not the badge of the West. Likewise, if there’s anything in the design that isn’t a green half-sun on a yellow field, it’s not the badge of the West.

As an example, the populace badge for the Kingdom of the West is “Or, a demi-sun vert,” or in plain English, the upper half of a green sun on a yellow field. If the charge isn’t a half-sun, or isn’t green, or if the background isn’t yellow, then it’s not the badge of the West. Likewise, if there’s anything in the design that isn’t a green half-sun on a yellow field, it’s not the badge of the West.

Unlike arms, a badge may be…

Fieldless: Many badges in period were fieldless; that is to say, they were physical badges that were pinned or appliqued to any number of surfaces regardless of that surface’s color. It’s best understood by thinking of the badge as a brooch. A badge may be fieldless if all of its component parts touch one another, but if it’s all in separate pieces on the field, it won’t hold together to be moved from one field to the next.

The populace badge of Caid, “Azure, four crescents conjoined in saltire horns outward argent,” can be fieldless because the four crescents touch one another (and, in fact, Caid has registered a fieldless version of the badge for their populace to use).

The populace badge of Caid, “Azure, four crescents conjoined in saltire horns outward argent,” can be fieldless because the four crescents touch one another (and, in fact, Caid has registered a fieldless version of the badge for their populace to use).

By contrast, the populace badge of Meridies, “Sable, a horse salient reguardant contourny between in chief two mullets argent,” cannot be fieldless because the horse and stars don’t touch one another.

By contrast, the populace badge of Meridies, “Sable, a horse salient reguardant contourny between in chief two mullets argent,” cannot be fieldless because the horse and stars don’t touch one another.

Tinctureless: A tinctureless badge is one that is undefined by any tincture at all. The badges of the SCA’s peerage orders are tinctureless, in that they can be any color at all (this is in contrast to some regalia which has specific colors attached to them).

The badge for the Order of the Pelican, for example, is “(Tinctureless) A pelican in its piety,” i.e., an adult pelican piercing its own breast and feeding blood to its young, below. The adult pelican, its offspring, their nest, and even the blood, can be any color or combination of colors.

Though the coloration of the badge to the right is unlikely, each peer is entitled to choose which color or colors to use to depict their display of their order badge. Thus, the badge of each order is registered as tinctureless, and is protected in all tincture combinations.

Like fieldless badges, tinctureless badges are defined by the charge type, number, and arrangement. The badge for the Order of Defense is “(Tinctureless) Three rapiers in pall inverted tips crossed.” If the charges are something other than three rapiers (or any kind of sword), if there are any number of swords other than three, if the charges are not arranged “in pall inverted” (i.e. an upside-down Y), or if the blades are not crossed at the tips, then it is not the badge for the Order of Defense.

Beyond being able to display the badge of the order, however, every peer is also allowed to include their order’s badge as an element of their arms2. This is called a…

Motif: A motif is a combination of elements (e.g. charges, tinctures, lines of division, etc.) that appear in heraldry as a set. Motifs of peerage order badges and regalia are reserved to those entitled to display them.

Motif: A motif is a combination of elements (e.g. charges, tinctures, lines of division, etc.) that appear in heraldry as a set. Motifs of peerage order badges and regalia are reserved to those entitled to display them.

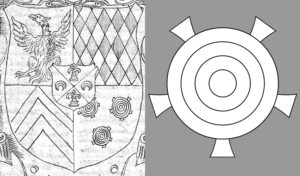

As an example, the badge for the Order of Knighthood is “(Tinctureless) A circular chain.” Knights may use this badge as a motif in their arms, frequently placing a loop of chain around the edge of their shield. To the right are the arms of one such knight who chose this option, Sir Saif ibn Sarim, “Gules, a Ukrainian trident head Or, on a bordure argent an orle of chain gules.”

As annulets and orles of chain have been the exclusive purview of Knights since the early days of the College of Arms, you can be sure that any closed and unadorned loop of chain in SCA armory is declaring that its bearer is, in fact, a Knight of the Society.

So, with all that covered, let’s design a badge for a peerage order.

So what are we looking for in a badge?

For a peerage order badge, there are elements that are required, and elements that are desired. It’s important to distinguish between the two. For example:

Required by the heralds:

- Follows style rules for SENA

- Does not conflict with existing armory

- Does not have a motif that already exists within registered armory

Desired by the Board and populace:

- Is unique, recognizable, and iconic

- Is aesthetically pleasing

- Is easy to reproduce

- Ties into some aspect of the Order, such as the name (laurel wreath for Laurel, pelican in her piety for Pelican, wreath of roses for Rose) or activity (rapiers for Defense)

The first three points are requirements to get through the registration process. They are objective measures within the rules of SENA. If there are conflicts with the design itself, the owner must be solicited to provide permission to conflict, or the badge will be returned. And if armory exists with the motif that the badge creates, it will give the unfair impression that the person is claiming to be a member of the Order.

The other four points are subjective and a matter of taste to many, but are nonetheless important to consider. If the populace struggles to recognize the badge, it’s not doing its job. If the members of the Order don’t like the badge, they won’t use it. If merchants or other artisans can’t make medallions or other regalia with the badge, Order members will find it difficult to mark themselves as members. And if there is no tie-in to either the name or the activity, the design will feel arbitrary.

Starting Simple

The ideal badge would be a single charge, never before registered. The badges of the first peerage orders (the annulet of chain, the laurel wreath, and the wreath of roses) follow this pattern.

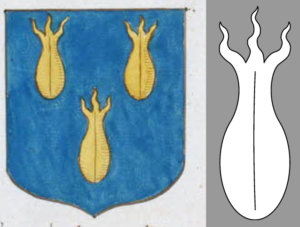

Several heralds habitually comb through period rolls of arms, looking for heraldic charges that are rare or unique to share with submitters. So the workshop team asked these armorial researchers to provide their collections with us. The following were some of the charges we considered, which are (as of this writing, August 2024) still unregistered:

This is by no means a definitive list of unregistered charges. Heralds find new charges regularly. However, as quickly as we find them, we also find submitters who are looking for something unique and interesting that reflects their interests. We’ll return to this later.

With these as our immediate options, we found that they were each lacking in some aspects. The sling staff is a weapon that some thrown weapons experts might use, and the spanning hook and spanning iron (as well as a goat’s foot lever, not pictured here because it is very complex to draw) are tools for loading a crossbow, but none of these are representative of the whole order. The other designs are not representative of the activity at all, and none of them really lend themselves to an order name like the Laurel or Rose. There aren’t many in the SCA would aspire to the Order of the Wound, and those that do might be reluctant to mark themselves with what appears to be a stylized Lovecraftian horror and is, in fact, a gaping wound spraying blood everywhere.

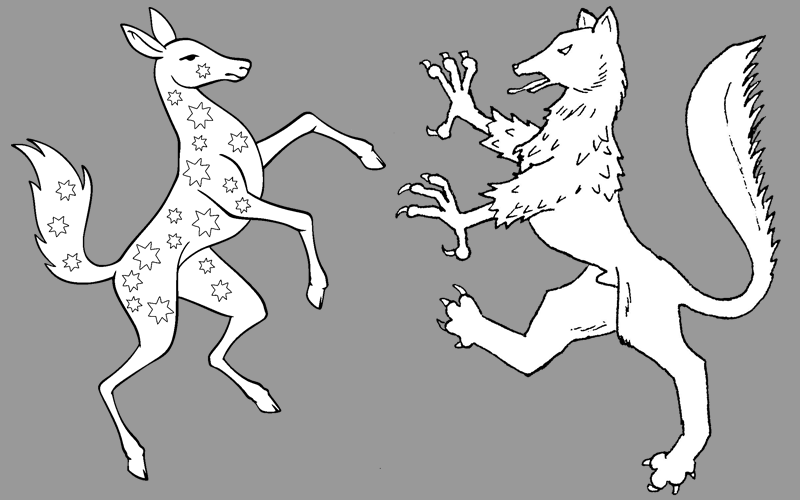

There was a charge that was discovered during the COVID-19 lockdown, a “marco,” which we thought at the time to be an archery target.

The team loved the simple, geometric beauty of the charge, as well as its flexibility in depiction, but by the time we were tasked with picking a badge, two submitters had already registered a marco, and there were two more in submission. Using the marco as a motif was already off the table. In addition, one of the submissions in process was just the charge, gold on a green and blue field, so the use of a marco on its own as a tinctureless badge was likewise impossible. Plus, a senior herald in commentary had discovered that our understanding of the charge was likely wrong, and that the design we thought to be an archery target was more likely to be nested scale weights, seen from above. The marco simply would not work as a stand-alone charge for the badge of the new peerage order.

So we returned to the drawing board.

Put Some Wings On It!

Unable to find a good option for a single default charge, we looked to modify an existing charge. Inspired in part by the wings around the mariner’s compass, and searching for a thematic link with ranged weapons, we looked at the possibility of adding wings to an existing charge. As one member of the team said, “the main commonality I see between the various martial disciplines in the proposed order is the use of something that flies through the air.”

We considered a few different ideas along this line, including a winged arrow (dismissed for the same reason as the slingstaff and crossbow equipment), a winged oak leaf, and a design combining three wings in a spiral. Towards the end of this phase, we seriously discussed the possibility of a winged mascle (a rhombus with the center removed) when it was pointed out that a solid rhombus (which heralds call a “lozenge”) has been used at multiple wars to mark ranged combatants.

Though there were no winged mascles registered or in submission, there were several winged lozenges and winged lozenge-like charges (such as a cushion and a passion nail) that gave us pause. We kept this design as a fallback option, but continued to brainstorm.

The Tower, the Tongue, and the Menagerie

With growing frustration over hitting multiple walls, the team hit a rapid-fire session of ideas, including more unused charges such as a helepolis (a siege tower on wheels), a “a mettalle balle of wyldfyer broken and blazinge,” and a tongue.

We also considered several unusual heraldic creatures, such as the pantheon and the enfield, both of which already had multiple registrations which blocked using them as a motif. We combed through bestiaries to find an animal that no one had claimed, but the longer we pursued that idea, the further away we found ourselves from iconic, recognizable creatures that the populace would embrace.

So many ideas which felt promising would end up having a conflict. Given that the College of Arms has been operating for nearly six decades, and has registered ~60,000 names and armory, it was clear that this task would not be as simple as it had been with the Orders established half a century ago.

Meanwhile, on Facebook…

While this was happening, the team was also monitoring various groups on social media as they, too, discussed possibilities for badges. On the Omnibus Martial Peerage group on Facebook, the central hub for the community dedicated to championing this new peerage order, the members had found the marco, and were discussing it as an exciting possibility for a badge. The research into the marco as a set of nested scale weights had not yet been made public, so members of the team shared what the College of Arms had discovered about the charge. Surprisingly, interest in the design did not noticeably fade, and as more of the ranged community came across it, they became more enthusiastic about it.

The excitement about the marco prompted the team to return to it as a central focus. Because it had conflicts on its own, we would need to find a way to add to the design in a way that didn’t spoil its simplicity. And the easiest way to do that would be to frame it within another charge.

The Marco and the Mascle

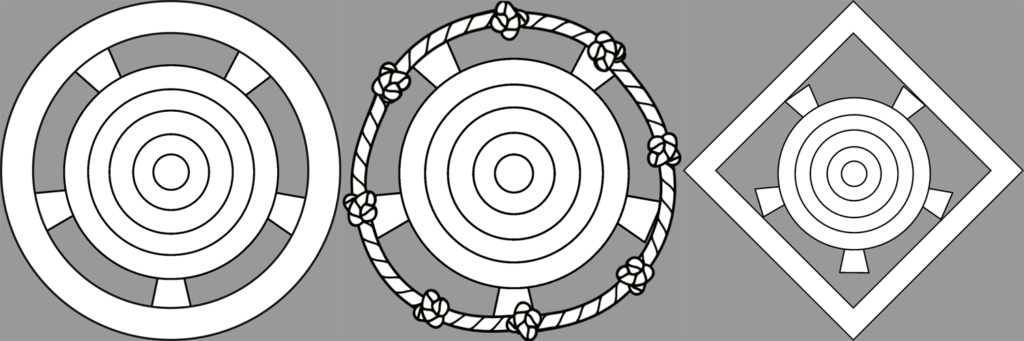

The team considered several frame-style charges, including an annulet (which made the badge look like a steering wheel) and a loop of rope with several knots in its length (which made the design feel much more complex than it needed to be). But ultimately, we returned to the mascle.

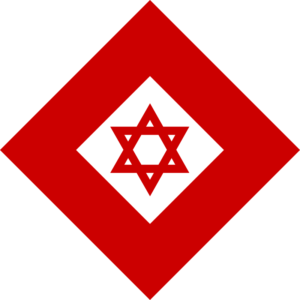

In this design, we had a combination of both combat and target forms of ranged martial arts. The mascle invoked the markings for ranged combatants, and the marco resembled an archery target. It wasn’t a perfect badge, but it was promising. When the team finally met in person to finalize the name, badge and regalia at KWHSS3, we were confident that we had found the right symbol for this new peerage order.

We Forgot About the Geneva Convention

This next section is going to take a bit of explanation.

In October 1863, an international conference of states and kingdoms convened in Switzerland to address the atrocities of war and establish a protocol to mark medical personnel on the battlefield. The Geneva Convention led to the adoption of a plain, equal-armed red cross on a white armband as the symbol of a medical non-combatant. Two years later, the Ottoman Empire ratified the treaty and established its own version of the marking, replacing the cross with a red increscent, also on a white field. Both of these symbols are protected by international humanitarian law, and are fiercely protected by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Any display of a red cross or crescent on a white field outside of their purview or context is prohibited.

What does this have to do with our badge design?

In 2005, a third emblem was added to the treaty for countries that do not have a majority Christian or Muslim population. Like our team, they sought a simple, easily recognizable design. And like us…they chose a mascle.

Countries and organizations with previously established aid symbols, such as Israel’s Mogen David Adom, are instructed to place their emblem inside the red mascle when working outside their own borders. So even though our mascle had a marco inside, it wouldn’t be enough to clear presumption with the International Red Crystal.

So That’s Why There’s A Fleur!

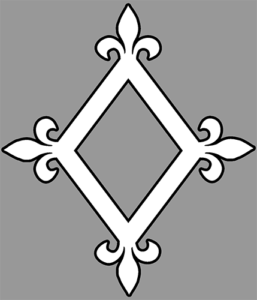

Once we realized our oversight, there was a new flurry of proposals to avoid violating international law. One solution offered was to use a period variant of a mascle, with fleurs on all four points. This variant is called a masculyn.

While fleury points make for a lovely design, we were aware that not everyone cares to be identified as masculine, even if the connection is only potentially implied. So we passed on the full fleury design.

However, the idea inspired several on the team to consider a single fleur on the top point. We discussed its resemblance to a compass rose, how direction and orientation are important to ranged martial arts, and how the fleur can be seen to direct the members of the order to a greater purpose. Thus satisfied, the team turned over the latest design to Laurel Queen of Arms for consideration.

The final design:

- Follows style rules for SENA

- Does not conflict with existing armory

- Does not have a motif that already exists within registered armory

And, just as importantly, the design:

- Is unique, recognizable, and iconic

- Is aesthetically pleasing

- Is easy to reproduce

- Ties into some aspect of the Order, specifically a combination of combat and target forms

Footnotes:

- The Board has chosen a different name for this Order, the Order of the Mark, at the April 12, 2025 Board meeting.

- except for Laurels, whose badge is used on arms to indicate official branches of the SCA, a concession that the Order of the Laurel approved when polled about the topic in 2010, because this practice is neither historical nor easy to make aesthetically pleasing

- the Known World Heraldic and Scribal Symposium in Philadelphia on June 28-30, 2024