Update: This article won the AS LVII Master William Blackfox Award for “Best Written Contribution to a Kingdom Newsletter” for its appearance in the April 2023 edition of An Tir’s The Crier.

This article is the second in a series covering the various types of heraldic flags found in the Middle Ages, providing enough of an overview to their use to inspire the reader to design and paint their own. Each article will describe the distinguishing features of the flag type, including their typical use in period, using examples from period art where available. At the end of the article, I will guide the reader through the process of designing a new flag using armory appropriate both to the SCA and history. This article covers the most prestigious and persevering heraldic flag: The banner.

A banner is a square or tall rectangular flag that displays the owner’s arms. They range between 3 and 5 feet to a side, and are frequently decorated with fringe and/or dags. Banners were used throughout Western Europe, and remained largely unchanged in form throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Earlier banners tended to be taller rectangles, following the pattern of the tall, narrow kite shields of the time. As shields widened and shortened, however, banners tended to follow suit, becoming more square in shape.

Banners marked the location of an important commander on the battlefield, and thus were a mark of prestige. Unlike the pennon, which was borne by bachelor knights (from the French bas chevalier, or base knight), the banner was borne by someone of at least the rank of knight banneret. In Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, he describes the ceremony of making a banneret:

Sir John Chandos advanced in front of the battalions with his [pennon] uncased in his hand. He presented it to [Edward the Black Prince], saying: “My lord, here is my banner: I present it to you, that I may display it in whatever manner shall be most agreeable to you; for, thanks to God, I have now sufficient lands to enable me so to do, and maintain the rank which it ought to hold.” The prince, [King Peter of Castile] being present, took the [pennon] in his hands, which was blazoned with a sharp stake gules on a field argent : after having cut off the tail to make it square, he displayed it, and, returning it to him by the handle, said: ” Sir John, I return you your banner. God give you strength and honour to preserve it.” (Sir John Froissart, Chronicles of England, France, Spain, and the Adjoining Countries, p.370)

Keep the Banner Displayed

Banners needed to be fully displayed regardless of the wind. Some banners used light fabric, such as silk, and relied on dags to help catch the wind and keep the banner displayed.

In most manuscripts, however, banners appear to be rigid, as if made of wood or metal. Even in action-based images that show other flags curling and waving in the breeze, banners look more like placards than flags.

While it’s possible that some of these field banners were made of wood or metal (see Vanes, below), their use on the battlefield is highly unlikely, as they would be horribly unwieldy. In another illustration from the same chronicle cited above, we see the banner of the city of St Gallen being torn apart in the middle of battle, so it’s safe to assume that most of these banners were made of fabric, such as linen or silk. So why do they appear so rigid and structured in manuscripts?

In his work, Heraldic Standards and Other Ensigns, Robert Gayre asserts that the top edge of banners were probably stiffened to keep them displayed:

“It is significant that banners were formerly, in France, stiffened along one edge, as will be seen from Fig. 46, of the Banner of France, from a medieval MS. This stiffening, no doubt, like the cross bar of the gonfannon, was to enable the charges on the ensign to be seen more easily…Most medieval representations show the banners outstretched, and it may well have been the general custom to stiffen them in order to display their colours.” (Gayre p.108)

However, other than a casual mention of a “top-bar-stiffened banner,” Gayre provides no evidence for historical methods for this. He doesn’t identify the manuscript he sourced other than “French,” and his Figure 46 provides nothing useful for banner-makers.

I’ve found only one example of an extant banner with built-in sleeves both at the hoist and the chief which support Gayre’s assertion. Oddly enough, it’s der Grosses Banner der Stadt St. Gallen, an iteration of the banner we saw being destroyed earlier. Made of painted linen, the banner has clear seamlines inset from the edge of both the top and left sides of the banner. The sleeves are easily visible due to their discoloration, and don’t interrupt the primary charge.

However, a common model for structured banners may be found in Japanese nobori, with a horizontal bar issuing from the top of the flagpole and attached to the banner with loops.

Modern prop departments have assumed that the Japanese external-frame technique is historically accurate, and we see it often in film and television. External-frame banners also appear in historical re-enactment groups, even those with stricter standards than the SCA. However, if it was used by Europeans prior to the 17th century, manuscript evidence suggests that the top bar was hidden inside the structure of the banner, rather than exposed.

Vanes

Some banners weren’t made of fabric at all. Heraldic vanes, the precursor to the modern weathervane, took the form of banners and pennons, made of painted and pierced wood or metal, and mounted to the peaks of castles and common buildings alike. In the image below from a 15th century French manuscript, fabric banners hang from poles in windows, while rectangular vanes fly from every visible peak. Take note that both visible buildings are hotels, not castles, and that the vanes likely have no relation to the current guests.

William Henry St. John Hope’s invaluable book, Heraldry for Craftsmen and Designers, goes into more detail on heraldic vanes, including fascinating information about the vanes of Hampton Court. I will also go into more detail about vanes in a future article.

Embellishment

While banners are among the most straightforward of the heraldic flags, they were frequently embellished with fringe and dags.

Fringe

Like most heraldic flags of high rank, especially in later period, fringe often adorned the edges of banners. The banners of the Order of the Garter were decorated with fringe “made of Gold or Silver and Silk, of the colours in the Wreath [livery].” (Elias Ashmole, The institution, laws & ceremonies of the most noble Order of the Garter, 17th century).

Schwenkels

A common embellishment of the banner was the schwenkel, a long single dag that extends from the top of the fly. Not much information exists about the purpose of the schwenkel. However, if we accept Gayre’s conceit that banners had rigid upper edges to keep them displayed, then the schwenkel might have originated as a sleeve to house the top bar. The schwenkel extends past the edge of the banner to at least 50% of the width of the main body.

Over time, the schwenkel became an integral part of many banners, present even without a rigid horizontal bar. Several texts mention the red schwenkel as a mark of particular distinction, and indeed there are several banners (such as Bavaria’s) which almost never appear without them.

Some schwenkels extended directly out of the fly of the main body of the banner, rather than a separate piece added to the top. We see one extreme example below, where the schwenkel is fully half the height of the banner itself, and twice as long as the banner’s width.

Sometimes, banners featured both fringe and schwenkel, to dramatic effect.

Multiple dags

Some banners featured multiple dags. More common in earlier period banners and seen often in pre-heraldic resources e.g. the Bayeux Tapestry, dagged banners apparently fell out of favor by the 13th century.

Materials

As mentioned above, banners were made primarily of silk and linen. The practicalities of the battlefield required sturdy fabrics and sensible construction. Much has already been written on painted banners, especially using Cennini’s techniques from Il Libro Dell’Arte. I recommend Compleat Anachronist 153, “Painted Flags of the Late Middle Ages,” by Master Rebecca Robynson (Shannon Miller) for more information on this matter.

Ceremonial use of banners in the 16th century allowed for more opulent fabric and surface decoration. For the installation of Henry III of France into the Order of the Garter, for example, Elizabeth I ordered that Garter purchase:

…as much Blue Velvet, Cloth of Gold yellow with works, and Purple Cloth of Gold, tissued with Silver, as shall serve to make one large Banner, richly embroidered on both sides, with the Arms of France…and that ye pay for the embroidering of the same Banner, for Purls of Damask Gold, and for Venice Gold Fringe, and Passamain Lace of Gold with Silk. (Ashmole, op. cit.)

Layout

Heraldry, as a general rule, expands and flows to fill all available space. Moving from the relatively triangular space of a heater shield to a rectangular shape of the banner requires some careful consideration in this regard.

Consider the arms of Bohemia: Gules, a lion rampant queue-fourchy argent, crowned Or. As depicted in the Zurich Armorial, the torso appears fully upright and parallel with the tail. One hind leg extends into the base point, while the other pulls in towards the body, following the curve of the shield. However, on a square banner, the torso shifts to a diagonal posture, with the hind legs pushing into the lower left and right corners and the tail filling the entire fly.

If charges are arranged in a default position (e.g. three items arranged two and one on an escutcheon) in registered armory, on tall banners the arrangement may shift to the default for that shape. See the arms of Herr Hartman von Aue on shield and banner, below.

Marshalled Arms

Banners frequently displayed quartered arms; that is, two or more sets of arms held or claimed by the same person. The armorial pairings were sometimes inextricably linked, as in the arms of Castile and Leon as borne by the Kings of Spain, or they could be displayed independently as well as quartered. Below we see the quartered arms of the duchies of Jülich and Berg, with an escutcheon of pretense for the County of Ravensberg. To the right, banners display the combined arms of Jülich and Berg, the arms of Jülich alone, and the arms of Guelders.

Sometimes, arms of spouses were impaled (displayed side-by-side) on a banner. Below is a sketch of a banner from a Tudor manuscript, displaying the arms of Henry VIII impaled with the arms of Catherine of Aragon. Each set of arms are themselves quarterings: Henry bears the arms of France quartered with England, while Catherine bears Castile quartered with Leon, Aragon impaled with Sicily, and Granada in base.

While many better-known arms were legitimately inherited, other quartered arms were assumed simply for the aesthetic of a banner. Ashmole informs us that this was a common consideration for new Knight-Companions of the Order of the Garter:

And because a single Coat was conceived not to stand fair enough in a Banner of this proportion, therefore the Soveraign hath been pleased (where a Knight-Companion wanted Quarterings) to grant a new Coat to bear in Quarter with his paternal Coat; as did King Iames to Robert Carr Viscount Rochester, afterwards Earl of Somerset; to whose paternal Coat he first added a Lyon passant gardant Or, in the dexter part, as an especial gift of favour, and then a new invented Coat to be born in quarter therewith, viz.Quarterly Or and Gules, a Lyon Rampant sable over all. He also granted to Sir Thomas Erskin (afterwards created Earl of Kelly) a Coat of Arms to be quartered with his paternal Coat, viz. Argent, a pale Sable. (Ashmole, op. cit.)

Related information available here: Marshalling in the SCA

How do I design my own banner?

Banners always display arms, either real or assumed. If you have registered arms in the SCA, you can put them on a banner.

First, choose the shape of your banner. Do you want a taller banner common to earlier period, or a square banner popular in late period? Where do you want to use the banner? Below are some templates from banners we’ve seen so far (click for a larger version).

Below are two examples of my own arms, as well as banners for the Kingdoms of Caid and An Tir. Caid’s arms have the crescents arranged and resized to fit the tall shape of the banner, while An Tir’s lion has been oriented like Bavaria’s, to better fill the square.

You can choose to display only your arms, or you might choose to marshall your arms, either by impaling them with your spouse/significant other’s arms, or by quartering them with one or more badges.

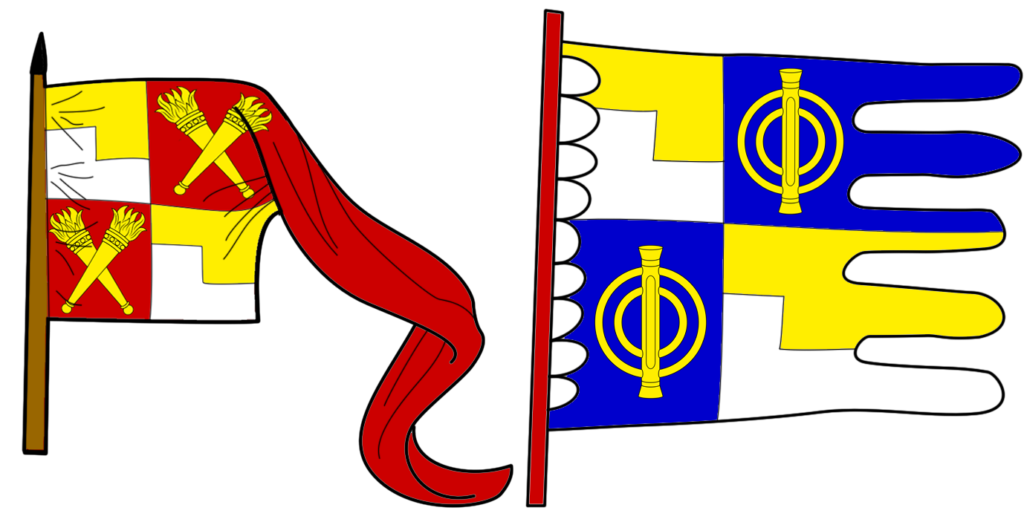

In the SCA College of Arms, heralds distinguish between devices and badges. The device represents the individual, while badges indicate ownership or affiliation. However, this distinction is largely administrative. In practice, the only difference between a device and a badge is that a badge can be fieldless (that is, it can be placed on any background). It’s a simple matter to take one of your badges, treat it as inherited arms, and quarter it with your arms. Below, I’ve quartered my arms with my crossed torches badge on a red field, and with my punner badge on a blue field.

Each quarter can be a separate design, and each can itself be quartered, which can be taken to ridiculous extremes. But with a little restraint, your banner will exemplify good period heraldic design.

What other kinds of heraldic flags are there?

For more information about heraldic flags, please see the options below:

Standard – A large, tapering flag used to display the badges of its owner, a rallying point for armies.

Pennon – A smaller flag used to display arms or single badges, great for battlefield identification

Gonfalon – A processional flag hung from a horizontal pole, can display arms, full achievement with awards, artistic motifs unrelated to heraldry